2020 panel discussion on Race—The Power of an Illusion, Part I

Episode 1

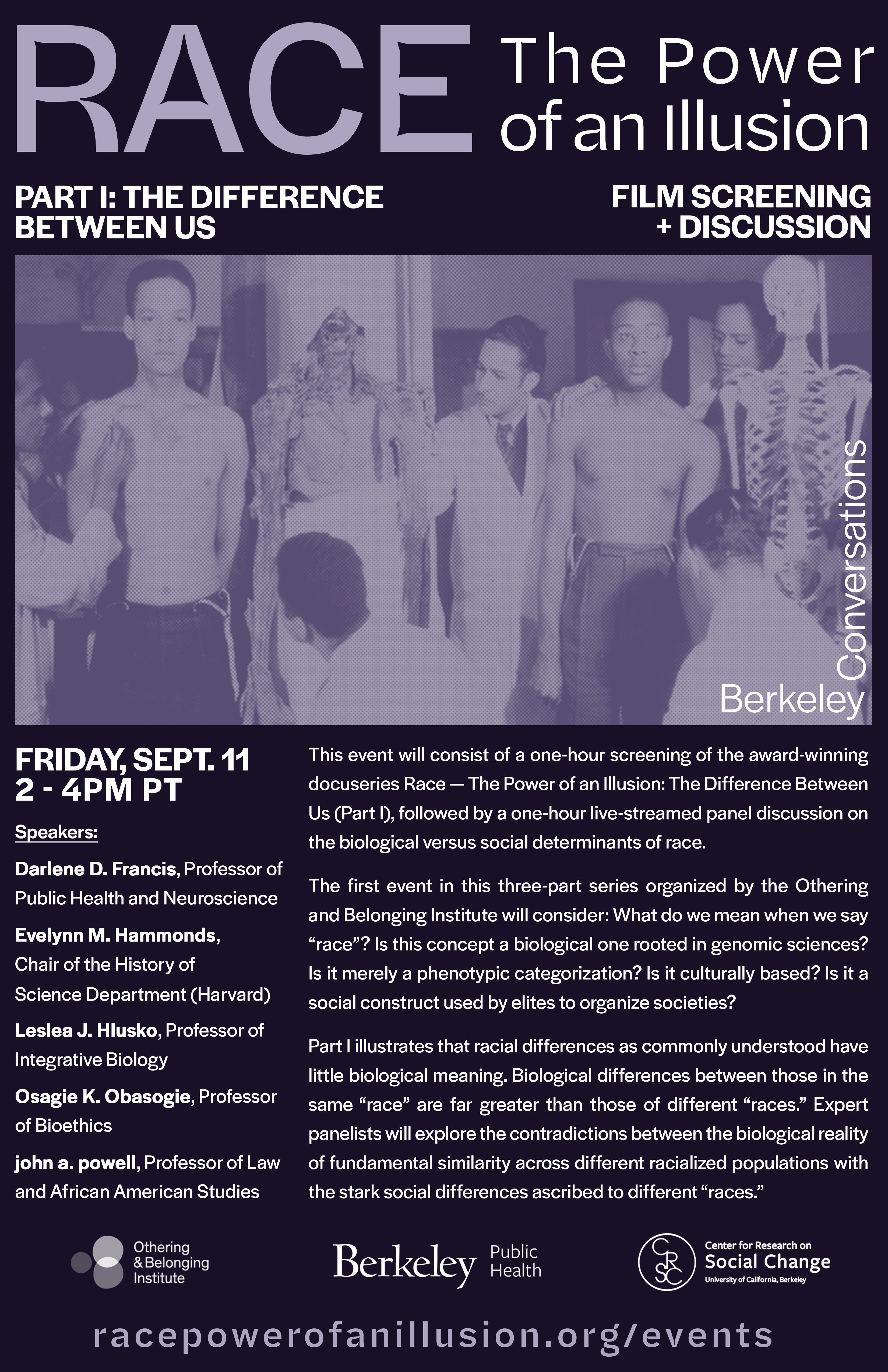

On Friday, Sept. 11, 2020 we hosted the first in a three-part series of events which consisted of a screening of Race—The Power of an Illusion, Part I: The Difference Between Us followed by a live panel discussion.

Part I seeks to reveal the complexities involved in what may appear to be a basic concept: What do we mean when we say "race"? Is this concept a biological one rooted in genomic sciences? Is it merely a phenotypic categorization? Is it culturally based? Is it a social construct used by elites to organize societies? The video shows interviews with scientists and ultimately illustrates that racial differences as commonly understood have little biological meaning -- We are all pretty much the same under the skin. In fact, there is greater genetic diversity within a racialized group than between groups.

Following the screening, expert panelists Darlene Francis (Associate Professor of Public Health and Neuroscience at UC Berkeley), Evelynn Hammonds (Chair, Department of the History of Science at Harvard University; Professor of African and African American Studies and interviewed in Part I), Leslea Hlusko (Professor of Integrative Biology at UC Berkeley), and john powell (Director, Othering & Belonging Institute and Professor of Law, African American Studies, and Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley) with moderator Osagie Obasogie (Professor of Bioethics at UC Berkeley School of Public Health and the UCB-UCSF Joint Medical Program) explored the contradictions between the biological reality of fundamental similarity across different populations with the stark social differences ascribed to different "races."

Our Part II (Sept. 25) event will cover the roots of race and racism in America, as well as how race is used to naturalize inequality. Part III (October 9th) will examine intersections of race with social institutions, power, wealth, and status. Bookmark this page for more information on the upcoming events. All events are free and open to the public.

(Scroll down for a transcript of the panel discussion)

Sponsors of the event included the Othering & Belonging Institute, School of Public Health, Center for Research on Social Change

Transcript

Osagie Obasogie:

Hello, my name's Osagie Obasogie, and I'm a professor in the School of Public Health and the joint medical program here at the University of California, Berkeley. It's my pleasure to welcome you to the first panel conversation on the video series, Race: The Power of Illusion, Part One: The Differences Between Us. So we'll be hosting two more screenings and panel discussions of part two and part three on September 25th and October 9th. I'd like to thank the sponsors for this wonderful program, the Othering & Belonging Institute and the Berkeley School of Public Health and the Center for Research on Social Change.

Osagie Obasogie:

So this documentary first aired in 2003 as a way to introduce people to the history of scientific racism and how developments in DNA technologies were upending lay and traditional understandings of race. This was a moment in time that shortly followed the announcement of the completion of The Human Genome Project, which mapped all the genes that make up humanity. This project was understood as showing in a definitive manner what social scientists have known for decades, that there is no biological basis for race.

Osagie Obasogie:

Race is a crude social and political category that does not map on the human genetic variation or population differences. At this time, many people expected race as an idea to dissipate and go away, given this new knowledge. For those of us who study race, we knew that this hope was a bit overly optimistic, even and perhaps especially for scientists who see their work as being driven by data and evidence. Race is about ideological and political commitments rather than any known facts. And sure enough, shortly after this announcement, we began to see new articulations concerning the biological significance of race that are just as troublesome as old ones.

Osagie Obasogie:

During this panel, we will revisit episode one of this documentary and try to understand its importance and limitations in light of various developments over the past 17 years. So today, I'm joined by an extraordinary group of experts who will focus on this issue, but first we have Darlene Francis, who is an assistant professor in the School of Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley. We have Evelynn Hammonds, who is at Harvard University and is the chair of the Department of History of Science as well as the Barbara Gutmann Rosenkrantz professor of the history of science and a professor of African and African-American Studies.

Osagie Obasogie:

We also have Leslea Hlusko, who's a professor in integrative biology at the University of California, Berkeley. And lastly, we have John A. Powell, who is the director of the Othering & Belonging Institute at the University of California, Berkeley, where he is also the Robert D. Haas Chancellor's Chair in Equity and Inclusion and also a professor of law and a professor of African-American studies and ethnic studies. So our first question for this panel will go to Professor Hlusko. So a lot of science has happened since the documentary has aired. What would you say has been the biggest scientific advancement in our understanding of race?

Leslea Hlusko:

When you started out, you made reference to The Human Genome Project. And we started with one human genome costing billions of dollars to sequence to today where you can sequence a genome for less than $1,000, and the ability to sequence that many genomes for very little money means that we now have full genomes, not just mitochondrial DNA sequences like they were talking about in the documentary, but now we have full genomes, three billion base pairs for thousands of individuals. And what this has really done is to tell us a lot more about what the structure of that genetic variation is.

Leslea Hlusko:

So the students had talked about and the scientists had made reference to human variation, that we need to be thinking about more that we're mutts, and mutts is a confusing term to use. It doesn't really make sense, because we can still see that people look different depending on what major geographic region you might be from, but what we've been able to find through this genomic variation at this large-scale sampling is that actually we all have four to six different populations represented within our genomes.

Leslea Hlusko:

And so, we have variation between people, but that you actually aren't just one lineage. You're actually a mix of different populations. I think this helps people understand why you can still see variation between people, between people from different parts of the world, and yet you still have most of that variation within those five major "racial categories" that people had created hundreds of years ago to be thinking about human variation. So the genomic evidence I think has really helped to further undermined but also refine our understand of human genetic variation.

Osagie Obasogie:

Great, thank you. And this next question is first for Professor Hammonds, and then we'll explore it with other folks, other panelists. So what updates would you make to the science portion of this film?

Evelynn Hammonds:

So I think the science portion of the film, like anybody would say, there have been a lot of advances in genetics and genomics. Leslea had just told us some of them, but at the core of it is still a concern to look at variation within groups and variation between groups, and how those groups are defined is still at the heart of the matter. And in some respects, how the population groups are defined can be problematic. And for the social scientists like me and Osagie and many of our other scholars, if the ways in which those populations are defined still carry a lineage or a legacy from the old notions of race, then we don't know how far we've come.

Evelynn Hammonds:

So of course, we need to update the science in the story of the film, but I don't think we need to change the experiment itself, because I think one of the virtues of the film and makes it so popular for 17 years, that's amazing, is because it captures young people at the age of... These are upper-class high school students, 16, 17, who are asking the right questions. They're still the right questions. And so, I think we need to update the test that they do and say more about what has happened since then, and we can do that easily, as Leslea also said, because it's much cheaper now to do it, but I don't think it would be right to change that, to put that experiment in the context of 17, 18-year-old students who are asking the questions, because I think that's one of the powers of the film and has made it so successful over time.

Osagie Obasogie:

Great, and do other panelists have ideas on what updates they might want to make to the science, if they were to do this film today?

john powell:

Osagie, I have one or maybe two. So first of all, I thank you and all the panelists for here today and for the discussion, and of course the filmmakers for making this I think really important film. I think one of the things we've learned a lot and that's become much more prominent since the film was made was basically understanding of a largely misunderstanding, the nature of the mind and the unconscious. And one of the things we've learned is... Social scientists, we've been talking about this for years. You don't see the world as it is.

john powell:

We're telling stories about the world, and those stories actually frame how we see the world. And we're meaning-making machines, individually and collectively. We're constantly making meanings. We have to make meaning. In part, that's one of the roles of religion, but it goes beyond religion into culture and art and other things, as well. And so, in a sense, we're looking for something for a reason. And I think it's important to dig into that more. And I think, as I recall, that's not critical in any of the three episodes.

john powell:

It's like, "What are we looking for?" It's like, "I'm still looking for the unicorn. I'm going to spend my whole life looking for a unicorn." Why? Because it gives me meaning. And in a society that's deeply, deeply racialized and deeply unequal and deeply hierarchical, and now with white supremacy resurging all the way to the White House, people are trying to like they did in the 19th century, grounded in pseudoscience. Since science is on the side of both equality in some ways, I'd say be careful with that.

john powell:

I think that science can't do all the work for us. We have to think about what our motivations are. Why are we so obsessed? And also at a time, not all bad news, that people are... Race is much more fluid and people accept that. Racial intermarriage and mixing is much greater, and that challenged these categories themselves. And that's going to continue to evolve. And so, the issue of contamination and one drop, a lot of people don't take that seriously, but then are still the people that's like, "This is the genocide to the white race."

john powell:

And then, the final thing I'll say is that this is a project of white supremacy. It's not just we're confused, and now the science is helping us straighten this out, no. What we're actually looking at is trying to refute this project of white supremacy, and I think the project in a sense has always been bigger than science or there have been times when science was an ally, but it's not just a scientific project.

Evelynn Hammonds:

Can I just add one word to that? John, you said this was science. I really try to get my students not to think about the old racial science and pseudoscience. It was real science. It was real science propagated by the leading scientific minds from the 19th century forward, and they didn't see it as bad science. They saw it as good science, good scientific questions, maybe bad methodology. Maybe people made some conclusions, but they didn't think it was bad science.

john powell:

Yeah.

Osagie Obasogie:

Right, right. No, these were people who were considered quite serious at the time making serious statements about the world. And so, it's important to understand that these were certainly ideas that were taken to heart. John, your earlier comments about thinking about how... I'm trying to remember that phrase you used, but understanding this race as a project of white supremacy. It's a conversation I had with my students yesterday in class, and one of the conversations we had was this idea that to think racially about the world is by definition a white supremacist project, that the only way you could think about the world this way is from a standpoint of hierarchical thinking about race to have privileges and prioritized in the interest of whites.

Osagie Obasogie:

And it was interesting watching my students grapple with that, to think about race as not simply some type of objective assessment of the world that is neutral, but rather as emanating at a particular moment for a particular purpose. And I think that once we are able to have that broader conversation to reorient people, that the very question of race, that is to think about the world in racialized ways, is part of that project, and we'll get to this conversation. One of the last questions I'll ask is back to Professor Hammonds, because she has this wonderful question or statement at the end of the film about unmaking race and racism.

Osagie Obasogie:

And I want us to spend some time on that at the end, but I think part of that is an acknowledgment of the origins of race and racism, and what its purpose was. It's part of that unmaking process, but we'll get to that in a few minutes, because I think that's an important conversation to wrap up with. Professor Francis or Hlusko, do you have questions or responses to this question about-

Leslea Hlusko:

Yeah, I'll jump in. Yeah, I just think it's also really important for people who envision the world from a scientific framework to also be thinking about how the scientists that were really establishing and propagating this idea that there are racial differences between groups of people. What they were really doing was looking for differences. And any time you go looking for differences, you can divide a group of students into two different groups and you can always find things that will differ between them.

Leslea Hlusko:

And biologically when you're looking at three billion base pairs, you're going to find genetic differences between them, but is it biologically meaningful? And so, one of the really important things that we're trying to do with the biological anthropology community and the people who study human evolution and human variation is to try to reframe this in realizing that the default assumption should always be that you're looking at one population rather than an assumption that you're looking at multiple populations.

Leslea Hlusko:

And that reframing really changes that more racialized perspective, but then the trick is if you can adjust this in the way the scientists are working, how do you get that message out to the larger community because so much damage has been done in giving people these ideas that racialization is biology. We have to figure out how to undo that in society, and that as has already been pointed out, that's really the trick.

Osagie Obasogie:

Professor Francis, did you have comments?

Darlene Francis:

I have lots of thoughts on the heels of what our fellow panelists have said, but completely in keeping with what they've all remarked upon. I agree with what Dr. Hammonds was saying, that I wouldn't change the narrative of this film at all, right? So we can plug in or plug out whatever scientific findings we've had in the last 20 years, but I relate to those kids, they're young kids in that video, so much and that was me, and I'm now a faculty member. I'm a laboratory bench scientist, and I study genes, and I study environment and I study individual differences.

Darlene Francis:

And not once, until I was in my faculty position designing a course where I really wanted to convey some of what we're talking about here to the students in front of me, I had never questioned the framing of the methods I was using, right? And so, we can talk about or mention at the very least Francis Galton, who was a eugenicist who framed the nature/nurture debate. And unbeknownst to me, I was working within this person's framework without awareness and working within a framework that I had inherited from my scientific upbringing and pedigree and training, which was not far away from the kids in this video 10 years out and I had never reflected.

Darlene Francis:

I had absolutely never reflected those constraints or how constraining that model was, which didn't suit me and it didn't suit the questions that I was asking, but I was happily working within that framework. And I would say that our pedagogy and our funding agencies are still saddled with that framework, right? So we still want to quantify genes for or genetic contributions to. We still have this divide between nature and nurture, or genes and environment, or experience and biology that is sometimes explicit but always implicitly captured in our approaches and our methods, at least from a scientific perspective.

Darlene Francis:

And it's not until I spend time or share space with folks who have a training and understanding of history, am I inspired to, I shouldn't say inspired, but am I reminded to question my frameworks. And I'm not sure that we do that well for our students, coming back to what Leslea is speaking to. Our pedagogy hasn't caught up certainly with the science and not the history of what we know.

Osagie Obasogie:

Right, I think that's a really good point, and both you and I are in the School of Public Health. And we are teaching students who are being trained in quantitative methods and statistical methods. They're being trained on how to think about the world in this quantified way as a way to improve health outcomes, but we don't necessarily teach them that the very methods that they're supposed to use to improve human health were developed by eugenicists for specifically eugenic purposes, right? So these are statistical methods that were designed with the very intent to be able to stratify populations in a manner that could allow resources to flow to those who are white and to take resources away from people of color and those deemed to be less valuable.

Osagie Obasogie:

And it raises important, not only methodological questions, but ethical questions. Should we continue to use these tools? And that is not a question that we have enough within our walls within the School of Public Health and within the field of public health and other fields that use these methods, and it's important to at least acknowledge where these tools are coming from.

Darlene Francis:

Yeah, I would just layer on top of that, that again this film is 17 years old, and I open my teaching in classes by turning everything upside down for the students. And I thought when I started teaching at Berkeley that I would be able to do that for a couple of years, right? This was after the sequencing of the human genome, and the implicit and explicit expectations that we would have the answers to all variability, because we would have the human genome sequence. We're incredibly special as humans. We would have hundreds of thousands of genes that's going to capture all variability, and I thought I could teach the way I was teaching for a couple of years.

Darlene Francis:

And 15 or 17 years later, I'm having the same discussions using the same tools, because our student body is not there yet. And so, we're not ready to let it go and move on, because we're not there yet 17 years later.

Osagie Obasogie:

Right, right. So before we move onto our next question, I just want to remind our viewers that you can submit questions for the panel that we'll get to in the last 15 minutes, and you can submit those questions on the Facebook Live comment section or on YouTube Live comment spots. So we'll start those Q&As with the panel around 45 minutes after the hour. So Professor Francis, we'll come back to you for this next question. So you've had a really interesting career.

Osagie Obasogie:

So you started off studying genetics, as you mentioned, and you now work in the field of neuroscience and study the social determinants of health. So can you talk about the shift in relation to some of the themes in the film that we see on race and biology?

Darlene Francis:

Yeah. So as I mentioned, I was those kids in that movie, and I grew up looking like this, a white kid in a family that identifies as black. And I was obsessed with science, and I really wanted to understand my place in my family but really my place in the world. And when I was a student in the '80s, late '80s and early '90s, in high school, really where you went to study, differences was you study genetics, right? So I started as an undergraduate studying genetics, and I should say that my father's African American or black from Canada, and my mother's indigenous First Nations, both from Nova Scotia, which have interesting racial histories, but I look like this and I've gone through the world looking like this.

Darlene Francis:

So I was interested in genetics for all the same reasons those kids in that film were making their cute predictions. And at some point, I recognized that the questions, that genetics was not going to answer my questions about my place certainly in my family, but bigger than that my place in the world. I wound up studying neurobiology in a stress lab, and the models that we were using were again framed by this nature/nurture paradigm where we were using various inbred strains of mice to identify group differences in stress reactivity.

Darlene Francis:

And the implicit and explicit assumption was that those genetic differences were responsible for differences in the stress response. So I did that work as an undergraduate. And then, during graduate school, I had the opportunity to really start asking different questions that were based on my own lived experiences, which the longer I was on this planet, I could better articulate, which is I really want to understand why my quality of life is so different from my sister who identifies as black and I identify as white, or the world certainly treats me like I'm white, because I know that we have the same shared genes.

Darlene Francis:

I know that at a biological level, we're no different. And so, what is it that could be explaining my different lived experience from my sister, who I'm so very close to? So I wound up studying neuroscience and became obsessed with understanding the brain as the site of transduction of lived experience. And along the way, the experiments that we were designing and conducting really, really were able to allow us to understand at a very proximate molecular, cellular level how different qualities of life and living and experiences using converging animal models was fundamentally influencing, not the genes that you inherited or that the animals possessed or the model organisms that we were working with, but how these differences in lived experiences were fundamentally influencing how those genes were regulated or expressed.

Darlene Francis:

So not looking at genetic effects but looking at epigenetic effects, so how experience is able to influence the genes that you inherit or one inherits. As a scientist, it was incredibly liberating to have the scientific understanding of, "Oh, I don't have to hunt for genes that don't exist to explain my different lived experience from my siblings, but certainly studying the stress reactivity or the stress response system and how different experiences impact that system absolutely helps me understand my path in life," which has been significantly different from my siblings'.

Darlene Francis:

And much like that kid in the video said, "It's not bad being white in this culture in society," right? My path has been that much easier based on lived experience relative to my siblings', and I can say that declaratively, and we can extract data from again converging model systems studying various components of the stress response and demonstrate that empirically. I have questions for some of our other panelists about again this need to biologize lived experiences, right? So we know at a very visceral lived experience level, that we all have different qualities of life and living, but once we can capture that biologically, all of a sudden people pay attention. And so, I'm really curious about that from my fellow panelists.

Osagie Obasogie:

Well, you anticipated my very next question, so I'm glad you raised that. So my next question was this issue of why are people so attached to biological determinism, and I think we can start with Professor Powell, and then we'll ask the other panelists as well.

john powell:

Well, it's interesting, like I suggested earlier that we are meaning-making machines. The world is. We've always been that way. That's what culture is. That's a lot of what religion is. There's a new study out showing that they think that maybe the story of Noah's Ark had a basis in reality in the sense that like now with our great fires, they were having great floods. It's like, "Oh man, the whole world is flooding. God's mad at us." They might not have said, "The arctic caps are melting," but they made some way of making meaning of it.

john powell:

And so, what we have, both in terms of early on but certainly now, we have these radically different lives. Professor Francis just talked about a little bit. It's interesting when you were saying lived experience. That's what it is. We have lived experiences, but we also live in a society built upon contradiction, as is much of Western society. So a society built upon the notion of, built upon the practice of, stolen land, stolen and enslaved people and freedom. And there's some suggestions that white supremacy and some of the more virulent expresses of white supremacy happened after the Civil War.

john powell:

So part of what we're seeing is justificatory system. We have to justify the world in which we live in, or maybe be uncomfortable or maybe try to change it. So if I'm walking past someone who's unhoused or homeless, if I'm walking past, driving in a neighborhood and all the houses are in disrepair, how do we make sense of that? And there are only a couple options, and Kendi talks about this some in the book about anti-racism. And one option is that there's something wrong with those people, and therefore, they're going to live in bad neighborhoods, and they're going to actually be homeless.

john powell:

When you look at what happened with George Floyd, and people are coming into this on their own, the trope that the dominant society keeps coming back to is we're all individuals. The police are good. Black people are dangerous. And so, when you hear about a shooting and the black community, we get up in arms or the white community by in large, I'm using generalizations, would be, "Well, what did he do or what did she do? What did that person who was killed by the police do?", and, "The police don't just kill people. That doesn't make any sense. There has to be some reason."

john powell:

There was about 10 minutes, and the right really went after discrediting George Floyd. He's an ex-criminal. He has a rap sheet. He's not a good guy. And given matters that he was a bad guy, a typical bad guy, and the police was trying to protect us from this typical bad guy. So why are we making such a big deal out of it? So the biological justification is the gold star. And if we can't have biology, let's use culture, but the point is we have to in some way explain why one person is living a life fairly comfortable, being treated well, and another group of people are not.

john powell:

And we see that again coming a lot from the political system. Something happens. I mean, it's so crazy. Think about this. President Trump argued that the reason there are fires in California was not climate change. It's that California run by Democrats, and therefore, the federal government should not put itself in position to extending resources to help with the fires. So it's the same kind of mindset, and I'll end just by saying this. I think one of the things we should be teaching students is the sociology of knowledge and the sociology of knowing, because we're already halfway when we just say, "Learn something."

john powell:

You're always in some type of methodology. You're always in some kind of framework. There's no, as we know, God's eye view. What does that really mean? So if there's no God's eye view, if there's no biological explanation, it's not simply what a society is teaching us, but why is some positions so attractive? Why do people keep organizing around them? What's that about? What's the social science about the willingness? You may remember Rodney King. When Rodney King was beat on the ground on all fours and they showed that photo, the first trial I remember, the police were acquitted.

john powell:

And the theme was Rodney King was a big black man. He had to be beat. The police weren't being brutal. This was a scary big black man. I think even one of the prosecutors actually asked the question, "What would be your reaction if you ran upon this guy at night in the streets?", and saying really to White America, "Aren't you afraid of this scary black man? Of course we have to beat him. Of course we have to contain them." So the biology of racism, the biology of difference, if we can nail that down, then all the stuff that we're doing in society in terms of racial stratification begins to make sense.

john powell:

And in fact, it not only makes sense. Those who would do otherwise, those who would invest in black people, those who would invest in Native people, those who would invest in Latino people, they're wrongheaded. They're wasting money. This is the natural order of things, and it's not only okay. It's appropriate that whites are the dominant group, and part of that's actually talked about in the whole ideology of meritocracy. You deserve whatever you are getting.

Osagie Obasogie:

Professor Hammonds, do you have thoughts on this idea of why biological determinism has been so sticky?

Evelynn Hammonds:

I agree with everything John just said. Biological determinism, it offers a naturalistic explanation for the social hierarchy that has prevailed in the United States since the founding of the Union, the founding of the United States. And so, that's why I teach the Notes on the State of Virginia, because in it Jefferson goes right to the heart of that. What is given by nature can't be changed. In that section where he talks about black people and the fundamental difference that makes them not the same as white people, he says that's given by nature, not by the state.

Evelynn Hammonds:

And the only thing the state has to do is... See, they're so fundamentally different from us by nature, by God, that we're just doing the right thing by keeping the... There's no way they could ever be us, because it's given by nature that we're fundamentally and inherently different. It is that notion of inherent difference that was inscribed in law and custom and practices in the United States and is supported by religion in certain times in parts of the 19th century and is undone in other ways by the ascendance of certain kinds of sciences, but then we get to Du Bois.

Evelynn Hammonds:

And I think I would say this is important to teach what John just talked about along with what Du Bois' whole program was for the social sciences at the turn of the century, at the turn of the 19th, into the 20th century. And it's all like, "Let's just stop this analysis talking about who black people are and what black people can do, and what black behavior is about or what black psychology is about based on these observations by white experts or non-experts, and just what they have to say." So one way he codified this was to say, "Well, if tuberculosis is a black disease and black people will die out because of the burden of tuberculosis on the black community," he says, "so what about the fact that if you go to Chicago and you look at the rates of tuberculosis among the immigrant populations who work in the stockyards? It's higher than the rates of tuberculosis for black people. So is this a question of race? And if it is, how is it?"

Evelynn Hammonds:

And he ushered in a kind of social science, not accepted in his time, and it was a great disappointment to him, but he was asking the hard questions. If it's about race, prove that it's about something you guys call race, and it couldn't be done and it can't be done, because then you have to interrogate what race is and you have to interrogate what systemic racism is. And I think an addition to the program, a separate episode, might be to talk about, as John said, the sociology of knowledge, the production of the facts that supported a notion of race as a natural category that then the state had to react to in particular ways, but of course the state was nominated by white males throughout the time of this formation.

Evelynn Hammonds:

And they went back to Omi and Winant who said, "Look, we're talking about something that was produced through a whole set of historical, social and political processes." Maybe that's another piece that we could do much more about that now and connect it to other aspects of the production of that kind of knowledge, which affected Native American peoples and immigrants through much of the 20th century, at least half of the 20 century, if not longer and we could do that. We could talk more about that, because I think the students for whom this film has been so useful need to have a way to think critically about this long history and how it shaped the world that we live in today.

Osagie Obasogie:

Thank you. Professor Hlusko?

Leslea Hlusko:

Yes.

Osagie Obasogie:

Do you have any additional thoughts on this question of biological determinism and why it's still with us to this very day?

Leslea Hlusko:

Yeah, thank you. Thanks for letting me chime in on this. It's just really wonderful to hear all of this, these comments and these thoughts. And as a scientist, I always am a little bit hesitant about trying to get into the minds and the motivations of scientists in the pat, but I would really like to pick up a thread that Evelynn had brought up earlier, that the scientist who really came up with this racialized biology, this was a really American thing. This was one of the early scientific theories that American scientists were widely recognized and praised for from the European scientific community.

Leslea Hlusko:

This is us. This is the United States scientific community owns this, and I think Evelynn's point that we need to be really careful or really mindful of the fact that these weren't bad people. These were the good scientists. They really thought they were doing good work. They were highly respected. From my personal opinion, my social science hat as opposed to my science hat, is that at the time there was so much inequity happening, because our country is founded on slavery as the economic base. And it's so unfair that as a scientist, if you look around and you see these inequities, you either have to say, "There's something fundamentally flawed with the people who have come up with this system."

Leslea Hlusko:

And being a white person, those are your people, right? Or you make the case that there's a biological justification for this, and then that makes you feel less bad like, "Oh, there's a reason. There's a biological reason for these inequities." And so, in some ways, I worry that the scientists who are looking for those differences, who are justifying them, starting way back a couple hundred years ago and you still see echos of this today, that it's people trying to say, "The people I know, the culture I come from, they're not that bad. They couldn't be that bad," because otherwise you have to say, "This whole system is rotten."

Leslea Hlusko:

And it's coming to terms with the whole system is rotten. And as Osagie, as you had pointed out earlier, perhaps we need to say, "Should we even use these analytical methods anymore, given what they were designed for?" I think our whole society is having this reckoning now. The whole thing is set up on this framework that is just mean and unfair, and basically demonstrating that there's no biological justification for this really then calls into critique this whole system that we're all a part of this, especially white people.

Leslea Hlusko:

We're so invested in this as our identity and having pride in that. And then, to have to come to terms with it's just rooted in really a mean economy, I think that's where it feels like we are now and trying to figure out how as academics and us as scientists can help move this process along and get into a better place. It's really poignant to be a part of this today.

Osagie Obasogie:

Thank you.

john powell:

Osagie, before we leave that, could I add two things?

Osagie Obasogie:

Sure.

john powell:

So one of the things, I mean, I think what was just said I think is really important. And one of the things you're saying, these were not bad people. I think you're right, but I also think we have to move beyond that frame. So was Jefferson a bad person? He's one of the founding fathers of this country. Was he a bad person? He definitely was part of a terrible system, and he wasn't just a part of it. He was the leading figure in that system, but again going back to what I suggested earlier in terms of Tilly, he says we're methodological individualists.

john powell:

We actually want to reduce this to individual behavior. And so many times when the police shoot someone running away from them with his hands up, part of the reframe is, "I know this policeman. He's a good guy." And I think that actually detracts from what's going on. It's what you said. It's like this is a system, and most of the people in the system are just doing what the system asked them to do. And yet, it's producing terrible things, and I just want to add one other complication to it. Another thing that makes it hard is when we think about our lived experiences, right?

john powell:

It's like how do I know this is right? My lived experience says this. We're not again recognizing that our lived experience is not a direct experience. It's mediated through structures and systems and narrative. Somehow in vernacular terms, most people believe if you're not a scientist, maybe even if you are a scientist, but if you're not a scientist, the pinnacle of accurate understanding is lived experience. Every black person I saw was a crook. That's my lived experience. It can't be wrong. That's my lived experience.

john powell:

I'm not a racist. I see that every day, and I know the police. I know the scientists. I know the professors, but it's actually more fundamental than even that. So I would just say not to be too distraught or disturbed by the fact that, yes, good people then and now will do terrible things and perpetuate a terrible system, and we have to figure out how to break that. And the lived experiences by themselves won't rescue us, because my guess is, and there's some social scientists that basically say, everybody believes what they're doing is right.

john powell:

No one thinks, "I'm violating my core fundamental principles." The young man who killed those people in the church was tormented a little bit, but he believed that as a protector of the white race, it was his job to kill black people. And he went so far as to say, "I didn't dislike them. Actually spending an hour with them, I thought there would be some people, but the higher calling was to still do that, not because I'm a bad person but because I'm responding to the gods of white supremacy."

Osagie Obasogie:

Right. And Professor Francis, I want to circle back to you and this question of biological determinism, see if you have any final thoughts on why it is still with us.

Darlene Francis:

This discussion is reflecting my experiences as a scientist, as a curious person in the world, as an academic grappling with all of these concerns myself and working within a framework that is historical and that doesn't speak to what I want to understand about the world. And so, again I've been asking questions of the panelists trying to understand that for myself. If I didn't know what I didn't know and it took me 30 years to even be exposed to any of this, to even question my own framework or scheme of going through the world, just like John was saying, how do we do better?

Darlene Francis:

My observation is that I have students who take one of my graduate courses, and they're specifically laboratory-based scientists who had never been exposed to any of the social theories or social history, or they're students who are coming from social sciences who have been afraid of biology. And this is probably similar to some of your courses, but this is the one space where we're even having these discussions. And I think back to Thomas Kuhn who wrote Structure of Scientific Revolutions while he was on the Berkeley campus, and it was a pretty pessimistic book. And his epilogue was really about until we have a common language and understanding-

Evelynn Hammonds:

I'm teaching it next week. I'm teaching it next week. It is pessimistic, yes.

Darlene Francis:

Well, it's part of what I've incorporated in my own understanding of how to... figuring this out as I go along. How do we think about this? And I think about the spaces that I hold for students. I'm just a facilitator of those discussions and share a little bit of information, but on our campuses, we don't have the pedagogy, unless you happen to find a course offered by somebody who gave a talk that resonated with you. We still don't 15 years in. I want to change my course. I can't, because what happens to this space?

Darlene Francis:

And it's still those divides. As academics or with our pedagogies and our institutions, not only are we doing a disservice to our students, but we are perpetuating what we're griping and complaining about, unless we tackle those concerns, but Kuhn followed up with that. His epilogue really gave me some hope, talking about the power of communication and language. We don't share space. And we have to be willing to engage and say, "I don't know." I'm a bench scientist. I was taught in graduate school how to pipette and make buffers, right?

Darlene Francis:

I went through a PhD program in a medical school and not once used the term race, talked a lot about genetics but certainly not race. Those students are still finding their way to me in classrooms and also medical students, not medical students but residents, physicians who are coming through and having discussions with their fellow students who have never been exposed to the concept of social determinants of how... And this is 2020 or 2019, the last time. So what are we not doing as academics, right? So that's why I'm trying to figure out, and we might be all in our own spaces figuring this out, but we shouldn't have to reinvent the wheel.

Darlene Francis:

And at a structural level, we have to address this. Otherwise, it'll be another 15 years. Evelynn looks the same as she did 17 years ago in that video. So otherwise, we'll have a fast-forward, but structurally unless we collectively figure this out and share language and share discourse, I don't know another way forward.

Osagie Obasogie:

Okay, great. Thank you. So the last question for this panel, and then we'll transition to the questions from the audience. We'll focus on this statement that Professor Hammonds made in the video where she says, "We made race. We can unmake it." And it seemed like such a straightforward, easy process, right? And I imagine over the years, you've been asked, "What does this mean? How do we do it?" So I wanted to give you an opportunity to explain that a little bit further and reflect on that 17 years after the fact.

Evelynn Hammonds:

It's very funny, because when the film first came out and my dad watched it for the first time, he said, "Why were you so angry at the end?" I said, "Was I angry at the end of that?", and he was saying, "Yes." And I said, "But I just said we made races. Black people didn't make race. Why you saying this?" So he was angry about what they were saying. It was very interesting. So the film, for me ..., it's personal, because there are pictures when I was nine years old with Life Magazine and tons of things.

Evelynn Hammonds:

And contrary to what Darlene said, no, I don't feel like I look like I did at that age and all of that. It was a throwaway line to say, "We made it. We can unmake it." I put myself in the we, in the community of scientists, social scientists, analysts. That's the we I was speaking to, though I was not explicit about that, and also we the people that the United States is structured by a racial hierarchy that we can unmake this racial hierarchy. We can stop it from being a way in which we distribute resources or opportunities or all the things that I think I look back as a historian to what the expectation was.

Evelynn Hammonds:

And the moment that I resonate most toward right now is the moment of reconstruction. The African Americans had been newly freed, and it's a moment when the war was barely over, and then the war's over, and then we have the period of reconstruction that goes into the 1870s, late 1870s. And the federal government realized that they had to take care of these people, because they had no food. They had no homes. They had no healthcare, nothing. At the time that that happened, there was also raging epidemics of smallpox and other diseases that were actually under control, and smallpox in particular.

Evelynn Hammonds:

And so, the Freedmen's Bureau was the first national effort to provide adequate healthcare to African American populations, and the African American leaders who were involved in that effort wrote to the government and said, "You have to do this, because it's a right of citizenship, and we're not citizens. So you need to do this." And of course, the history shows that the federal government finally retreated. There was a huge fight. You can read all the history if you want, and the Southern states won and we entered our 1900 into the period of Jim Crow, of disenfranchisement from the body politic.

Evelynn Hammonds:

And science played a role in that, and the notion of fundamental difference was actually amplified in yet another way. If these people are biologically deficient in some ways, then we shouldn't extend full rights to them as people. My interest is in trying to bridge for students that step from the scientists who provided who are living in their time, but not only that but who wanted to provide a naturalistic explanation for what was a draconian set of social policies and not just draconian, horrific because people died.

Evelynn Hammonds:

There's no way that I could have said all of that in that moment, so I just did this throwaway line and said, "We made it. We can unmake it," but we can unmake it. We can't ensure that scientific explanations of human variation do not serve to support national policies to disenfranchise people who are marked as different or other, and that their otherness and their difference is the root cause of the situations that they face. Like I said, I couldn't have said all of that, but one of the great things about the film over this time, literally a year and a half ago, I was walking across Harvard campus, going somewhere else and a student said, "I just loved your lecture today."

Evelynn Hammonds:

And I said, "I didn't lecture today." "Oh, the film, the film." I said, "Oh okay." "But what did you mean by the unmaking?" And I said, "I meant we can think ourselves to a different place. We can think about the long terrible history of the use of race as naturalistic, biological to another place of understanding real social determinants of health and biological differences. And the other thing I forgot to say is human variation is real. Variation within a species is real. It's real. Of course we're going to be different.

Evelynn Hammonds:

It doesn't mean that difference is deficit. Science has in many ways, and this is a broad generalization and I'm going to get killed for it, but some sciences have stood on the side of difference is deficit, but difference is difference. In other species, difference is difference. And so, I think that it's a moment where we can, if we study hard our history, if we understand our social science, if we really as Darlene said, Darlene didn't hear about any of this stuff for a very long time, that scientists and humanists and social scientists and artists and regular people know more about this, we can think ourselves out of the structures that we in fact created.

Evelynn Hammonds:

Of course, you can't do that in a film in the last five minutes. So I did what I could, and I was happy that they sent me back my Life Magazine book, Time Life Magazine book where I was sitting as a kid when I was nine years old to close the circle, but that's where I was coming from. And I probably should write this, because I get asked all the time, but it's really meaningful to me. And perhaps, ending with a shorthand like that is probably not the best thing to do today.

Osagie Obasogie:

Well, thank you for that. So we have about a little less than 10 minutes for questions from the audience. So I'm going to read, hopefully try to get through, a few of these questions. This first question I think is really useful for this panel, since we're all academics. So the question is what or who are the obstacles today to correcting our shared understanding of race in the academy?

Evelynn Hammonds:

Wow. That's-

Leslea Hlusko:

[crosstalk 00:56:35].

Osagie Obasogie:

We could have an entire panel on this, a separate hour-long panel on this I think, but if-

Evelynn Hammonds:

Leslea is ready to do that one.

Osagie Obasogie:

Yeah, folks, have quick responses. I think it'd be useful for folks to have some insights on what's happening here in academia in these topics.

Leslea Hlusko:

So one quick response from me is as a biologist is seeing that we have these silos in the academy that you're a social scientist. You're a biological scientist. You study in the humanities. There's these silos and we have our students take classes in silos, and there's very few opportunities to really explore the space between the silos. When you talk about human biology and human biological variation, it exists smack in the middle of the humanities, the social sciences and the biological sciences.

Leslea Hlusko:

And until we all get everybody on campus and not just those of us who are listening to this webinar or who are part of this, but everybody gets comfortable with being in the space in between, I think it will be very difficult to get over the hurdle.

Osagie Obasogie:

And are there obstacles outside the academy that we should also flag and be mindful of?

Evelynn Hammonds:

Well, I think some of the issues outside of the academy, which you may know about Osagie, today a number of social scientists and scientists pinned a letter that was published in Science Magazine today that asked the NIH and other leading scientific organizations to really do a deep dive and study of the continuing use of categories of race in science, and it's time to do that interrogation. I don't know if you know the number, but there are a number of really... Many, many people signed onto that, that it's time to do that. It's a moment of reckoning, so it's time to do that.

Osagie Obasogie:

Do others have thoughts on obstacles inside or outside of the academy?

john powell:

I have a couple. One, we don't have agreement. We do speak different languages. We have different motivations. We have different orientations. First of all, the meaning of race and racism has constantly shifted, and that's practically the work of Michael Omi, Howard Winant. So it's not one thing. It was Malcolm X that says, "Race and racism is like a Cadillac. You get a new one every year." So we're not talking about one thing.

john powell:

So think about this. We had our first black president, and then we get Donald Trump. So there's this constant back and forth. And when you talk about a project, which we have a little bit, it's serving some people. And Steve Martin makes the observation, two observations. One, he says, "It's not just a question of conflict of interest. We're talking about conflict of being. We're talking about anthological questions, because people inhabit race in such a way that... Such as white people, not all white people but many white people, that's where they get their sense of being from.

john powell:

So when the Proud Boys say, "You will not replace us," they're talking about not losing my job. They're talking about losing their sense of who they are. So literally, you have from the far-right now this constant talk about genocide to white people and that they, we, they have to fight back. And so, Steve says playing off of Marx, Marx made the observation that marriage is a relationship between two men mediated through a woman. And he says race or whiteness is a relationship between white people mediated through people of color, particularly blacks.

john powell:

This is largely about reconstructing the white identity. And I would say in part, it's hard for us to imagine a different white identity. So what we have is that we have this white identity or like the Proud Boys, we have genocide. So what would a different role and identity and being, anthological being, for white people be? And to me, that's not so much a scientific question as a potentially spiritual and religious question. And I'll just end by saying religion, and Dr. Hammond talked about this a little bit, religion plays a huge role.

john powell:

There are times when the science wasn't on the side of racism. The people turned very much to religion. And so, what we see now is that religion, if science is in the way, for a lot of people they just reject it. This is deeper than science, so those are some of the barriers.

Osagie Obasogie:

Okay. Well, thank you, John. And on that note, we are coming up on the hour. So we have to end the conversation here. So I want to thank all the panelists for joining us and for their excellent thoughts. And for the audience, I want to remind you that we have two more video screenings coming up that examine the following two or last two episodes of the documentary. Episode two will be September 25th from 1:00 to 3:00 Pacific Time, and episode three will be October 9th from 12:00 p.m. to 2:00 p.m. Pacific Time. So once again, thank you very much and hopefully we'll see you in a couple weeks.

Evelynn Hammonds:

Thank you. Thank you so much.